No further performances this season.

We are the hope ourselves

Christian Spuck in conversation

Michael Küster & Claus Spahn (MK & CS) Christian, how did your first Requiem production come about?

Christian Spuck (CS) In a survey by the Opera House Magazine for the 200th birthday of Giuseppe Verdi, I mentioned that the Requiem is one of the most moving works for me personally, and I would be intrigued to choreograph it for the stage. Shortly after, Andreas Homoki [the Intendant] came to my office and said, «We absolutely have to do this!»

MK & CS What is your personal connection to the piece?

CS I first heard the Verdi Requiem on the radio when I was 17, and I found it so fascinating that I recorded it with my cassette recorder. It was the legendary Toscanini recording. At that time, I had to write a paper on Franz Kafka, and I spent nights on it while always playing this Requiem music in the background. Nothing progressed without it. That was a very subjective first encounter with the piece in a highly emotional phase of my life. Even though my engagement with the work goes much deeper today, I still feel this very personal connection.

MK & CS What relevance does the religious background have for you?

CS In the Requiem, it's generally about humans grappling with death. About the big questions: Who are we? Where do we come from? Where are we going? Reflecting on the finitude of existence, we confront ourselves. In the face of death, humanity looks at itself, and I believe, in this sense, Verdi, who was critical of the church, also composed his Requiem. He uses the Latin text from the Catholic liturgy, but his requiem mass has a secular character and is not a holy mass in the church's sense. His Requiem is traditionally performed more in the concert hall than in the church. This is no coincidence. He aims more for the universal human than for the concrete religious message of the text.

MK & CS What does the text mean to you then?

CS I find it very problematic because it essentially formulates a single big threat: Man is led before the punishing God and judge on the Day of Judgment, who opens the book of sins and either admits him to heaven or sends him to the damnation of hell. Man constantly appears as a trembling creature, pleading for mercy and longing for redemption. Threatening with God's wrath, the «Dies irae,» was a proven power tool of the Catholic Church. But Verdi wasn't concerned about that at all. The music doesn't reflect that either; it's not primarily about fear. It tells of tender moments of seeking solace, letting go, human community, and hope in the greatest moment of pain. For example, the «Lacrimosa» with its beautiful, far-reaching melody is, in my opinion, genuine mourning processing.

MK & CS But the «Dies irae» has an Old Testament weight.

CS Sure, it's very theatrical. You can feel that Verdi was an opera composer. The music is incredibly effective. But I don't perceive it as intimidating in the sense of the text. For me, it's more the terror of death itself, its relentlessness, that is expressed in the music.

MK & CS So, can it be said that in your stage version of the Requiem, you interpret not the Catholic Mass text, but the music?

CS Absolutely! That's very clear to me. When we rehearse a new scene, I always read the text again in the hope of discovering something in it that I can bring as motivation into the action on stage. But the work opens up to me purely through the music again and again.

MK & CS What makes the Verdi Requiem suitable for a scenic implementation?

CS The music doesn't need visualization; it can stand completely on its own. That's why I constantly asked myself: Is what we're doing here right? What can I derive a necessity for? Will we do justice to the music?

MK & CS What is the biggest danger in visualization?

CS That you start telling stories. That you show people standing at the grave or similar things. Any attempt to load gestures with narrative meaning goes in the wrong direction. That diminishes the work's message and quickly ends up in kitsch. The path to scenic realization leads only through abstraction. My wish is to develop sixteen large tableaux that react to the music, add something of their own, have scenic power, and make the audience hear the music differently.

MK & CS Does abstraction exclude emotions?

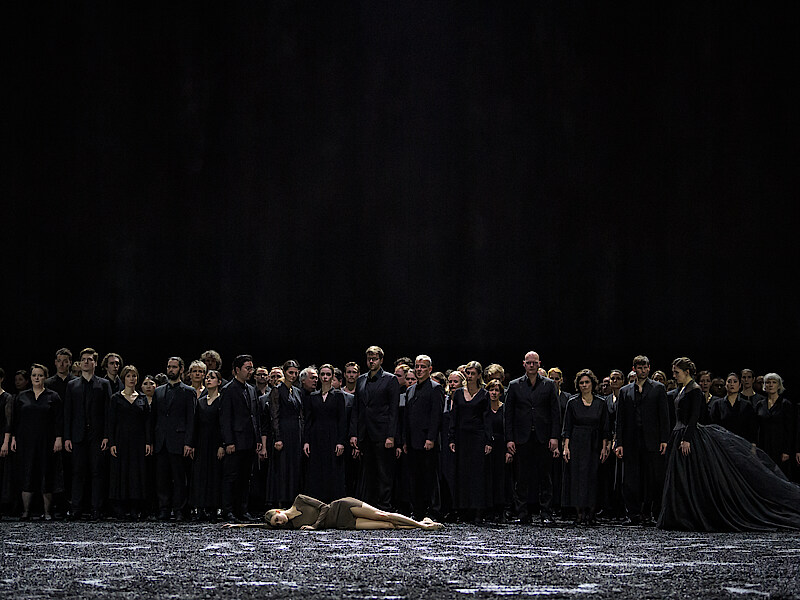

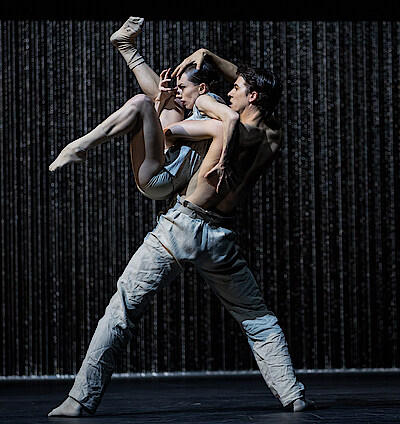

CS No, of course not. I naturally want to bring the emotion inherent in the music onto the stage. And it is conveyed by the performers — by the dancers, by the solo singers, by the choir, by the orchestral musicians. It's very important to me that everyone on stage doesn't play roles but are humans, being themselves. That's a central theme in all rehearsals: Everyone is themselves. The emotion of the music passes through each and every one in their entire artistic individuality. This applies to the dancers as well as to the singers. Dance and song are quite similar in their expression: they move beyond text and meaning. They are abstract languages that tell much more than can be expressed in words. The beauty of singing and dancing lies in their ambiguity, and that is important to me in my Requiem staging. I want the audience to read in the images what they want to read into them themselves.

MK & CS Isn't it particularly difficult for the singers not to play «anything»?

CS Yes, that's true because they are used to always thinking in terms of roles and searching for a dramatic motivation for every gesture and movement. But what I'm specifically aiming for is that they don't, for example, portray specific scenes of mourning. Moreover, we have it easier there because we always develop the movement material abstractly at first. Only when it comes to developing characters do we use the material to shape characters. That's why dancers find it easier to just be on stage and express the emotions as they feel them.

MK & CS You are trying in this production for a scenic combination of singers, dancers, and a large choir. What artistic energy can be gained from this constellation?

CS The desire to intertwine dance and song is actually always doomed to failure. You can try it, but a real fusion is not achieved because that would mean the singer is dancing and the dancer is singing. In my choreography, singers and dancers sometimes touch or give each other gestural impulses, I can hardly go further in my abstract interpretation. But a lot happens in rehearsals between the otherwise separate departments. The choir, solo singers, and dancers inspire each other, give each other energy, pay respect to each other, which results in scenic tension. I find this very beautiful. When the choir began to sing the opening bars of the Requiem in the utmost pianissimo for the first time in rehearsal, they were completely moved by it, and conversely, the concentration in the movements of the dancers transferred to the choir, who were standing still. That a shared artistic energy develops, a connection, a sense of community. You feel how everyone is there for each other. I really enjoy working with the choir. It has an intermediary function because it sings but is more playfully active than the soloists. It can appear as an anonymous mass, but also as a large group of individuals. The choir has a great handling of abstraction, which is what I'm looking for.

MK & CS How did you start working on the staging?

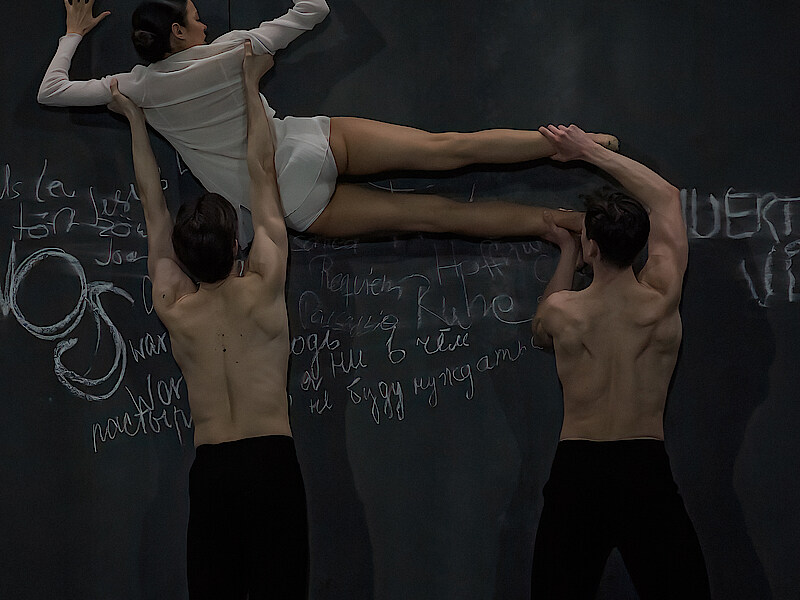

CS I went to the ballet studio, picked out individual pieces of music, and just started choreographing. Then we left what we had worked on, picked it up again, and changed the music to the movements or vice versa. We often rearranged the pas de trois at the beginning of the «Quid sum miser» and thought about it in different ways. It was a constant process of searching, approaching, and discarding. I allowed more doubts in this production than usual, and with the dancers, I preserve the freedom not to make a final decision. The solo singers and the choir joined later, and we continued searching together.

MK & CS The entire ballet company is cast in the Requiem, and many dancers have solo tasks. What motivated you to do this?

CS I wanted the whole company to be involved in this production because it unites so many different personalities and temperaments. Every dancer is capable of expressing Verdi's music in a very personal way, and I wanted to use that for the production.

MK & CS In what space is a scenic performance of the Requiem conceivable?

CS Christian Schmidt, our set designer, has designed a large, enclosed, dark, empty space. There is no heaven above the ceiling, and no hell under the floor. The people in it are thrown back on themselves. There is black snow, which looks like ash, and little light. Something terrible seems to have happened, something that affects everyone together and each individual separately. What exactly it is, doesn't matter. Since we're dealing with a Requiem, one can assume that there is a loss to mourn or an encounter with death has occurred. We don't know more.

MK & CS Does Verdi's requiem mass offer comfort to humanity?

CS After the horrors of the «Dies irae,» the piece becomes noticeably calmer and also strikes touching lyrical tones. But the «Dies irae» keeps coming back and unfolds its full force again in the final «Libera me.» We know that this «Libera me» is the core of the entire Requiem. Verdi composed it first and then created the other parts from it. In particular, the final fugue stands oddly against the previous parts. In key and how it was composed, it has something very life-affirming and worldly and knows no reaching out to religious heights. But at the very end, the soprano sounds again with a pleading gesture. With it, the dark, sad, and lonely return.

MK & CS So, does a sign of hope stand at the end?

CS I might not stage a sign of hope. But the fact that there are people articulating what moves them deeply is of course an enormous sign of hope. There is no other reason for hope than ourselves.

Quoted from the programme booklet, 2023. The conversation was conducted by Michael Küster and Claus Spahn in 2016.